Photo of the Care Rx Nanaimo Team (Left to Right: Dena Taraschuk, Hafeez Dossa, Leigh Palmer, Chloe Kim)

A case for deprescribing PPIs for patients without documented indications for the anti-reflux medications

By Hafeez Dossa, BSc

Abstract

Objective: The utilization of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) was reviewed in a long-term care (LTC) facility setting, as it was noted that many residents were taking these without documented indications. Through a pharmacist-led intervention at four LTC facilities across Vancouver Island, we aimed to re-evaluate the appropriateness of PPI therapy across all patients.

Methods: This six-month intervention looked at all residents serviced within four LTC facilities across Vancouver Island who had an order for a PPI on their medication profiles. Upon categorization of each resident, based on indication (or lack thereof), letters were sent to the prescribing physicians outlining a summary of recommendations with the aim of reducing inappropriate PPI usage. Results were collected after the four-month mark, and a follow-up report was generated two months later to identify the effectiveness of recommendations (i.e. to see if patients remained off PPIs, or if they were restarted).

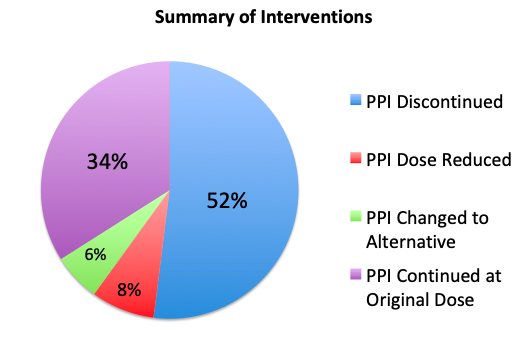

Results: Out of 370 residents, 99 had an order for a PPI at the beginning of the project (27 per cent). After accounting for residents who were either discharged, or passed away during the study period, 88 remained eligible for follow up. Of these 88 residents, 46 had their PPIs completely discontinued (52 per cent), seven had their dose reduced/changed to PRN (8 per cent), and five were switched to an alternative medication (6 per cent). Overall, out of the 88 residents who were followed in this study, 57 of them (66 per cent) had their PPIs successfully deprescribed.

Conclusion: A pharmacist-led intervention in a residential care setting can dramatically reduce inappropriate use of PPIs. This allows for a reduction in the risk of harmful adverse events, unnecessary drug spending, and workload on nursing staff for medication administration. Clear communication and collaborative care are factors that influence the promotion of such initiatives, and the success of this project should help influence other pharmacists and health-care professionals within an interdisciplinary care setting to consistently re-assess the necessity of all medications.

Have you ever wondered why so many patients are taking proton pump inhibitors (PPIs)?

It is estimated by the Provincial Academic Detailing Service that 1 in 12 British Columbians receives a prescription for a PPI in any given year. Whether in a community, hospital, or residential care setting, there’s a large number of patients on PPIs, and oftentimes we may not be exactly sure why they’re being taken.

Although these anti-reflux medications can be effective in reducing symptoms of heartburn and acidity, with long-term use they do also carry a risk of adverse effects, including an increased infection risk (pneumonia and C. Difficile), an increased risk of fracture, and reduced vitamin/mineral absorption. In the elderly population, this is especially important to note, as contracting pneumonia or experiencing a fracture can be a traumatic event and patients may not be able to bounce back.

In an effort to reduce unnecessary PPI usage amongst residents living in residential care facilities, my team at Care Rx in Nanaimo and I undertook a pharmacist-led initiative to deprescribe PPIs currently in use.

Starting in January 2019, we ran a report of all residents serviced by the pharmacy (approximately 400), and noted that 27 per cent of them had an order for a PPI. After looking through these patients’ charts, and consulting with nursing staff/physicians, these patients were then separated into one of the following five categories (percentages of residents in each category are listed in parentheses):

- A Resident taking PPI with no documented indication (38 per cent).

- B Resident taking PPI with no documented indication, however as they are also taking a long-term ASA/NSAID, we would like to confirm if this is the indication for therapy (18 per cent).

- C Resident taking PPI with no documented indication, and is taking ASA for primary prevention. As ASA has a higher risk/benefit ratio when used in primary prevention, we would like to re-evaluate therapy of both ASA and PPI (2 per cent).

- D Resident taking PPI with documented indication of GERD. In these residents, we wish to follow up and re-assess if therapy is still required (32 per cent).

- E Resident taking PPI with a significant diagnosis for use (i.e. GI bleed history, Barrett’s Esophagus, etc.) (10 per cent).

Although a daunting task, individual letters were then sent to physicians indicating which category their patient was in, the risks associated with long-term PPI use, and a list of recommendations for deprescribing of PPIs, if appropriate.

This included options such as tapering the dose, switching to a safer alternative such as ranitidine, or changing from regular dosing to PRN (as needed) use. After making recommendations, receiving responses from physicians, and processing the orders, we then waited two months to make sure patients didn’t experience any rebound effects from being taken off their PPIs. Approximately 5 per cent of patients re-started their PPIs after they were discontinued, which we thought was a reasonable number for this sort of initiative. A two-month waiting period seemed appropriate as previous studies have used a 4-8-week window to monitor for rebound effects after stopping PPIs. By July 2019, this project was complete.

The results were astonishing: 52 per cent of patients had their PPIs completely discontinued, and another 14 per cent either had their dose reduced or switched to an alternative medication. Overall, only 34 per cent of patients continued on their previous dose.

Below are some examples of cases where a PPI was discontinued, indicating the reasoning for the PPI being started and measures that led to successful deprescribing:

- Resident A, an 87-year-old male, was taking pantoprazole 40mg daily. He had been taking this dose since admission to the care facility (over five years ago), and there was no documented reason for the use of this medication. He was not taking any other medications that could have contributed to symptoms of GERD, such as ASA or other NSAIDs. We recommended discontinuing this medication with a two-week taper, where 40mg of pantoprazole was taken every other day, and it was then stopped. During the two-month follow up, he didn’t experience any symptoms of GERD and this was documented as a successful discontinuation.

- Resident B, a 64-year-old female, was taking rabeprazole 20mg daily. Upon review, it was noted that this medication was started two years ago as she was experiencing GERD. During consultation with nursing, it was noted that she had not recently exhibited any symptoms of GERD, and that it would be appropriate to consider discontinuing this medication. We recommended discontinuing this medication with a four-week taper, where 20mg of rabeprazole was taken every other day, and it was then stopped. We encouraged lifestyle modifications if there were any symptoms noted, however during the taper there were no issues and this was documented as a successful discontinuation two months later.

If more than 60 per cent of patients didn’t need to be taking their PPI at their original dose, how does this end up happening?

Prescribing inertia is a real thing. Patients may be started on a medication, and then not given any guidance on whether or not they should be taking them long-term. This is especially common in residential care, where patients are admitted into care with a list of medications, and continued on them after a physician signs off on their previous list of medications. It’s also common for patients to be discharged from hospital on PPIs, as they are often used as protocol to reduce reflux/heartburn associated with laying flat during a hospital stay. Community patients may also use PPIs regularly to treat reflux, as they may see them as an easier fix in comparison to lifestyle modifications such as eating healthier (limiting consumption of large meals, reducing alcohol/caffeine intake), being physically active, and ensuring not to eat prior to lying down.

The success of this initiative received high praise from the care managers of the facilities who were included in this initiative.

“Having been at this facility for over 20 years, it’s no secret that many of our residents, and those at other facilities like ours, are overmedicated,” says Lydia Swift, a registered nurse and director of care at Chartwell Malaspina Gardens. “Polypharmacy is a serious issue, and PPIs are a great place to start. An initiative like this has shown everyone how important the role the pharmacist can play in an interdisciplinary team.”

Sheryll Southern, registered nurse and director of care at Trillium Woodgrove Manor, shared a similar sentiment.

“These patients need pharmacists to advocate for them. So many times we have patients come into our facility and they stop receiving the attention and care they should be getting in order to ensure they’re taking medications they actually need. Seeing over 50 per cent of PPIs get completely stopped shows how important it is for us to always be re-evaluating medications our patients are taking.”

Not only does this initiative reduce the risk of side effects and pill burden, reducing the use of unnecessary medications also helps save costs. In residential care facilities, many medications are covered by PharmaCare Plan B, which is a government plan that helps cover the costs of many common medications. However, PPIs are only covered through Special Authority, which means a physician needs to submit an application to PharmaCare indicating that a patient requires the medication. This means that in a lot of cases, PPIs come at a cost to patients, and as shown in the results of this project, over half of patients didn’t need them in the first place.

To paint a picture of what this would look like in B.C., take the following into consideration: In the patient population under discussion, 27 per cent had an order for a PPI. There are approximately 30,000 publicly-funded residential care beds in B.C., and so if we were to extrapolate this across the province, we could say that approximately 8,000 residents are taking PPIs. If 52 per cent of them are able to have them discontinued, that means over 4,000 patients would be able to successfully stop taking PPIs.

Sounds like a lot of people, doesn’t it? But what about the cost? PharmaCare will cover the costs of PPIs, if Special Authority is approved, for approximately $1.50 per week, which adds up to about $80 per year, per patient. If you were to take this number and apply it to all 4,000 residents in our theoretical tally, this results in a cost savings of over $300,000 annually.

This is only for those living in publicly-funded residential care facilities; this does not include private facilities, hospitalized patients, and community patients. Although this is using a fairly small sample size and extrapolating this data across the province wouldn’t likely end up being representative of the actual numbers, it’s not completely unreasonable to assume similar results if we were to utilize a similar approach across the province.

In summary, deprescribing initiatives have the ability to result in significant cost savings to both the government and patients, while also reducing the risk of side effects and limiting polypharmacy. All it takes is spending a bit of extra time in reviewing patients’ medications and working with patients and prescribers to ensure appropriate medication usage.

When telling people about this initiative, the first thing they usually say is not that they’re surprised we were able to stop PPIs in over 50 per cent of patients, but how impressed they are that we were able to get everyone on board with it. Working with nurses, physicians, dieticians, and other health-care professionals is awesome, and everyone has been very supportive of us in taking on projects such as this one. But our team at the pharmacy is equally as important too, and they’ve also given us every opportunity to successfully complete these types of projects. Having to fax letters and document changes on a spreadsheet may be frowned upon by some, because it’s extra work above and beyond what is expected. However, there’s a shared desire to optimize medication usage and it’s this passion and work ethic that allowed such an initiative to be so successful.

As pharmacists, we are the most accessible health-care professional. We see patients when they come in for their refills, we sit down with patients when we do their medication reviews. We should absolutely be educating our patients on the risks and benefits of all medications they are taking, and the results of this project shows why this is so important.

Hafeez Dossa is the Pharmacy Manager for Care Rx Nanaimo, a pharmacy that services over 400 patients who live in long-term care and residential care facilities. He is passionate about optimizing medication management, and this project is just one of a few initiatives he has taken on during his time working in long-term care (others include re-evaluating approaches in anti-hypertensive therapy and re-assessing treatment for patients with dementia). A 2017 UBC Pharmacy graduate, Hafeez also enjoys playing hockey, participating in triathlon events, skiing, and checking out local breweries.