Every month, the BC Drug and Poison Information Centre receives on average 230 calls regarding medication errors occurring at home.

BC Drug and Poison Information Centre pharmacist Dorothy Li offers a review of pharmacy’s most common patient-induced therapeutic errors and how pharmacists can help avoid them

Pharmacists routinely deal with medication errors (MEs), which often occur during medication prescribing and dispensing. Safe dispensing includes use of the “5 rights” mnemonic: right patient, medication, dose, route and time/way. But many MEs occur after our patient leaves with a correctly prescribed and dispensed medication. This article discusses how patients commit MEs and what pharmacists can do to reduce them.

Medication errors in B.C.

Every month, the BC Drug and Poison Information Centre (DPIC) receives on average 230 calls regarding MEs occurring at home. In 2018, this represented 9.7% of total calls. The majority (97%) were patient or caregiver initiated errors: 66% in adults, 30% in children 0-12 years and 4% in adolescents. There were no reported deaths, although 15% were referred/presented to Health Care Facilities (HCF)* and 5.3% had moderate or major effects. Of adults ≥ 60 years, 23% were referred/presented to HCF. Most common MEs in all age groups were: wrong medication given/taken, medication given/taken twice and other incorrect dose. Additional common MEs in children ≤ 5 years were: confused units of measure and incorrect formulation/concentration administered. The top drug classes were analgesics, cardiovascular drugs, antidepressants and hormones (insulin, oral hypoglycemics, biguanides and thyroid preparations).

“Double dosing” medication errors

An adolescent accidentally took 600 mg of bupropion XL and was referred to the emergency. She had been taking 2 x 150 mg tablets for one month. Following a switch to 300 mg tablets, she erroneously took 2 tablets, out of habit. A seizure occurred at 11 hours. This patient had no known risk factors for seizure except the double dose of bupropion, a narrow therapeutic index (NTI) drug. She knew how to take her medication but made a slip or “action-based error.”

Drug shortages, which can necessitate changes in medication strength, may place patients at risk for double doses. Heightened awareness coupled with careful counselling on the potential effects of double doses for NTI drugs may prevent similar MEs.

Among 876 double doses reported to U.S. poison control centers from 2006 to 2015, life-threatening symptoms occurred in 12 cases (1%): bupropion or tramadol — seizures; beta-blockers or calcium channel blockers — bradycardia, hypotension and heart block; and propafenone — ventricular tachycardia. With intensive care, all recovered. Moderate effects occurred in 206 (25%) cases, most commonly with calcium channel blockers, beta blockers, alpha-2 agonists, amphetamines, antidepressants, atypical antipsychotic, analgesics, insulin and sulfonylureas. While this double dose study reported no deaths, a larger U.S. study of MEs including all types of errors occurring outside of hospitals reported a death rate of 0.02%.

“Knowledge-based” medication errors

Two weeks after a new prescription for methotrexate and prednisone, a patient in her 90s presented to the emergency with profound mucositis. Misunderstanding the instructions, she took 5 mg of methotrexate orally each day (rather than once weekly as prescribed). She received IV leucovorin, filgrastim (G-CSF) and a blood transfusion for pancytopenia. Morphine and nasogastric feeds treated her mouth pain and dysphagia. By day 21, she was able to eat for the first time.

Advanced age, polypharmacy, new prescriptions and complex drug regimen of an NTI drug were risks for this ME. This error was “knowledge-based,” resulting from not understanding how to safely take her weekly methotrexate and the dangers of daily dosing. Strategies to avoid this type of ME include careful counselling using the teach-back technique and encouraging questions by asking, “Do you have any concerns about your medication?” The Institute of Safe Medicine Practice further recommends limiting methotrexate quantity to 4 weeks, folate supplementation, regular laboratory monitoring and specifying a particular day of the week in the directions.Methotrexate MEs resulting in life-threatening effects is not a new problem. Life-threatening pancytopenia and death occurs with as little as 3 days of consecutive dosing or a cumulative dose of 40 mg. The case above was one of 66 reported to DPIC over 7 years. The majority of these cases occurred at home (92%). The most common errors were: daily instead of weekly dosing (29%), doses too close together (27%) and incorrect amount (24%). Many patients were referred/presented to hospital (42%) and received intravenous leukovorin (24%) and G-CSF (8%). Risk factors included: new prescription, dose or route change, or complicated regimen (36%); elderly (32%), polypharmacy and multiple disease states (29%). Isolated cases involved communication problems (language or hearing) and cognitive issues.

Prevention

The majority of MEs at home do not cause injury. A few result in major clinical complications and some in death. The pharmacist’s goal is to reduce harm associated with MEs. Regulatory strategies have effectively reduced MEs with cough and cold preparations in preschoolers. Proven frontline strategies include: pill organizers, improved patient information, helping patients calculate and measure liquid doses, active participation in treatment by patients, encouraging questions to resolve doubts, motivational interviewing technique and phone apps.

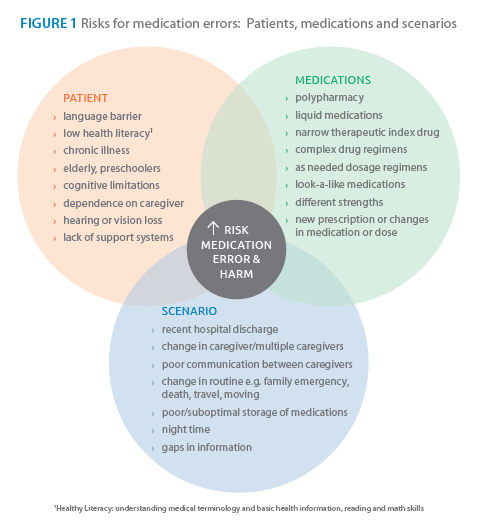

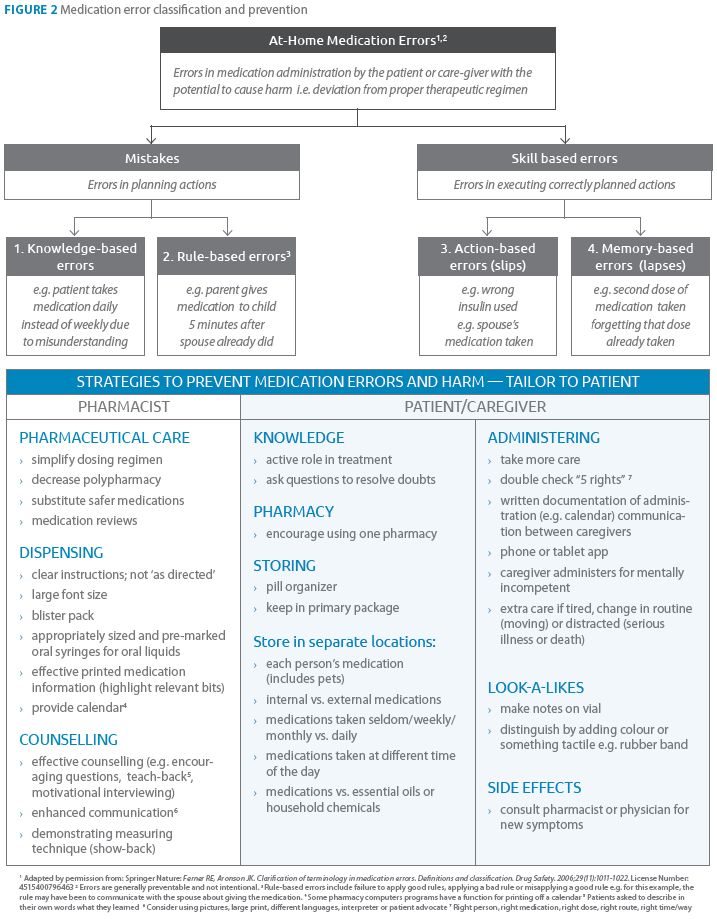

The role of the pharmacist in medication safety now goes beyond the “5 rights.” By identifying patients, medications and scenarios that have an elevated risk of ME the pharmacist can tailor ME prevention strategies during the process of pharmaceutical care, dispensing and counselling (see Figures 1 & 2). For NTI drugs, extra care in counselling at-risk patients and using teach-back technique to determine the patient’s level of understanding is essential. In case of inadvertent ME, call the Poison Control Centre for immediate risk assessment, recommendations and management.

*HCF = mostly hospitals, also physician’s office and medical clinics.

An expanded article with additional examples and references will be available at dpic.org.

Written by Dorothy Li, B.Sc.(Pharm), CSPI, BC Drug and Poison Information Centre. Reviewed by C. Laird Birmingham, MD, MHSc, FRCPC. Acknowledgement: Victoria Wan, Biostatistician for BC Centre for Disease Control