Sponsored by Duchesnay

By Jane Xia, Bsc.Pharm, PharmD, MBA, RPh

There are more than 180,700 unintended pregnancies annually in Canada, associated with direct costs of over $320 million (1). With the expanded scope of practice in B.C., pharmacists are now able to prescribe and dispense all contraceptive options (2). On top of this, most contraceptives are fully covered by PharmaCare to improve patient access (3).

With such a positive shift in the system, pharmacists now have a valuable opportunity to support patients in their contraceptive choices. But we also face a multitude of challenges when it comes to selecting and prescribing oral contraceptives in a busy community pharmacy setting. Time is limited, there’s no standard protocol or checklist to guide the conversation, and the overwhelming number of products on the market doesn’t make it any easier. On top of that, we’re expected to tailor choices to different patient profiles, address concerns about side effects, and support special populations like adolescents or postpartum patients.

Although combined oral contraceptives (COCs) and Progestin-Only Pills (POP)s demonstrate a comparable contraceptive efficacy under typical real-world use conditions, COCs often remain the default. It is important to keep in mind that COCs may not always represent the most suitable choice for all individuals. Progestin-only options, though sometimes overlooked, offer safe, effective, and increasingly relevant alternatives that can help us meet the diverse needs of our patients. POPs have fewer contraindications. They can be safely prescribed for patients and are contraindicated in only 0.6% to 1.6% of women. In this article, I’ll explore the barriers we face in practice and highlight key information on the different options available in Canada, as well as emerging tools and strategies, especially around progestin-only pills, that can support more confident, patient-centred prescribing.

To start off, I’d like to briefly go over how COCs, which contain both estrogen and progestin, help prevent unintended pregnancy from a mechanism-of-action perspective. To keep it simple, progestin is the primary hormone responsible for preventing ovulation, while estrogen plays a secondary role by inhibiting follicular development—though its contraceptive effect is less prominent than that of progestin (4). From a practical standpoint when prescribing, progestin provides the main contraceptive action, while estrogen is included primarily to help regulate menstrual bleeding (4).

Progestins remain the key hormone in preventing pregnancy—whether used alone or in combination with estrogen. Most progestins work by stopping the body from releasing the hormones needed to trigger ovulation. They do this by suppressing signals from the brain that normally tell the ovaries to release an egg, for example drospirenone. However, not all oral progestins fully suppress ovulation. Some progestins, such as norethindrone, primarily exert their contraceptive effect at the local pelvic level, by thickening the cervical mucus to block sperm from entering the uterus, slowing down the movement of the egg by impairing fallopian tube motility, and thinning the uterine lining (endometrial atrophy), making it less suitable for implantation, and only secondarily at a systemic level (6). For example, studies show that up to half of women taking norethindrone may still ovulate while on the pill (7).

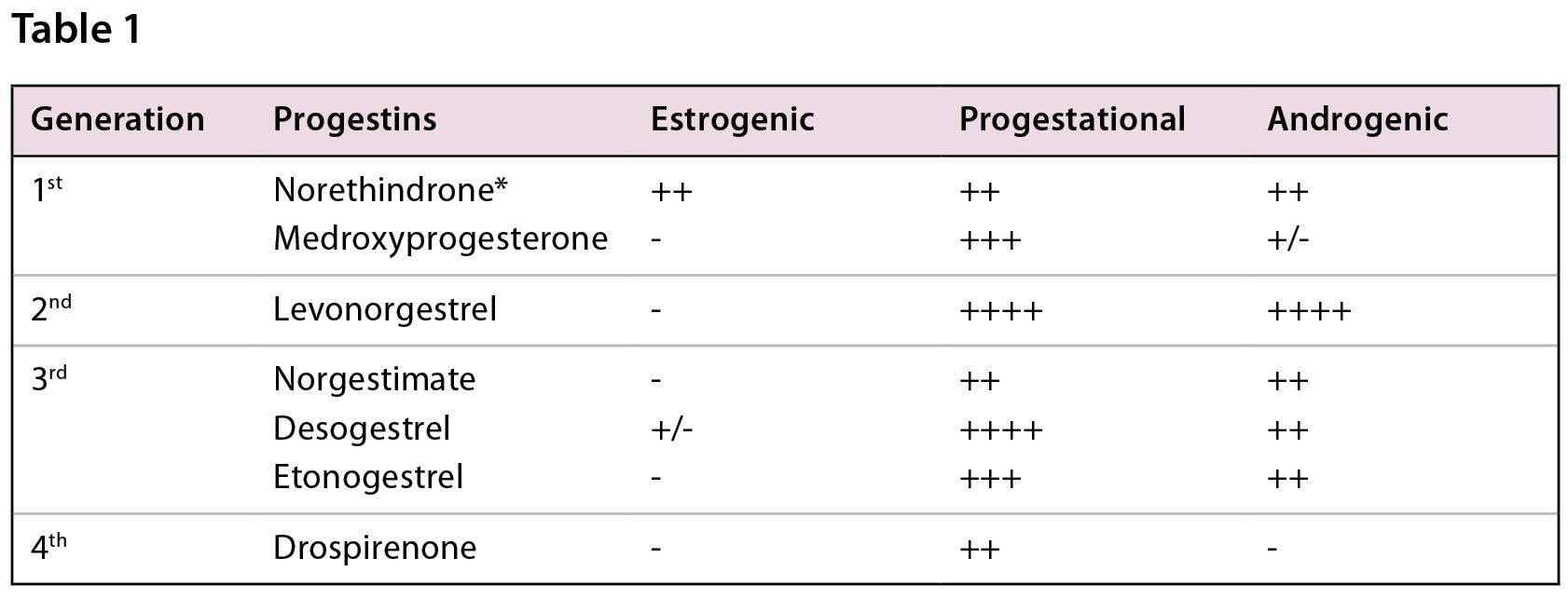

While there’s no shortage of contraceptive products on the market, when it comes to oral contraceptives, both combined and progestin-only, we’re really dealing with just a handful of progestins in routine practice. Understanding their differences is key to guiding patients effectively. Table 1 shows a quick summary of commonly used progestins, grouped by generation, and their characteristics without the influence of estrogen (15). Keep in mind: the addition of estrogen tends to lower the androgenic activity of certain progestins and can help improve cycle control.

*Note that the androgenic activity also varies based on the dosing of the progestin (Norethindrone 0.5mg <1mg) (Table adapted from resources 15, 17)

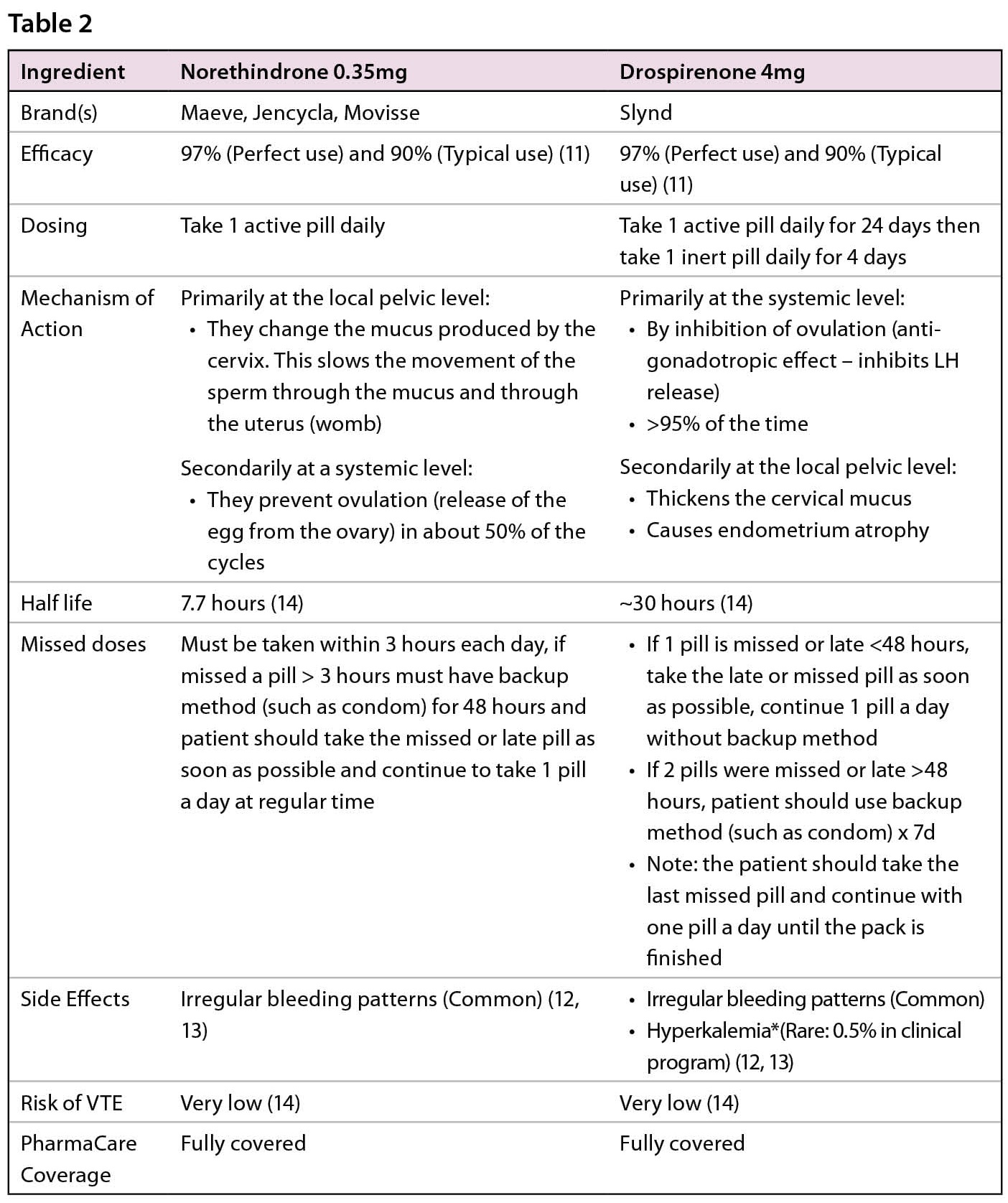

With this foundation in mind, we will now review the progestin-only pills (POPs). In Canada, there are only two progestins that are approved for use as POPs. Namely, Norethindrone 0.35mg (Brand name Maeve, Movisse or Jencycla) and Drospirenone 4mg (Brand name Slynd).

To start off, the Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada explains that the use of progestins in progestin-only options administered in contraceptive doses does not appear to increase the risk of venous thromboembolism, myocardial infarction or stroke, or decrease the production of breast milk. World Health Organization also recommend POPs in a wide range of patients with many conditions such as hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, smoking, obesity, breastfeeding migraine with aura, inherited coagulation abnormalities factor V Leiden mutation, Protein C and S deficiencies. These guidelines reassure us of the safety profile of these products (16).

There are some differences between the two different progestins. Please see Table 2 for comparison.

*There is a potential for an increase in serum potassium concentration in women taking drospirenone (Slynd) with other drugs that may increase serum potassium concentration. Drospirenone (Slynd), a progestin, which has anti-mineralocorticoid activity, including the potential for hyperkalemia in high-risk patients, comparable to a 25 mg dose of spironolactone. Drospirenone (Slynd) is contraindicated in women with conditions that predispose to hyperkalemia. (12, 13)

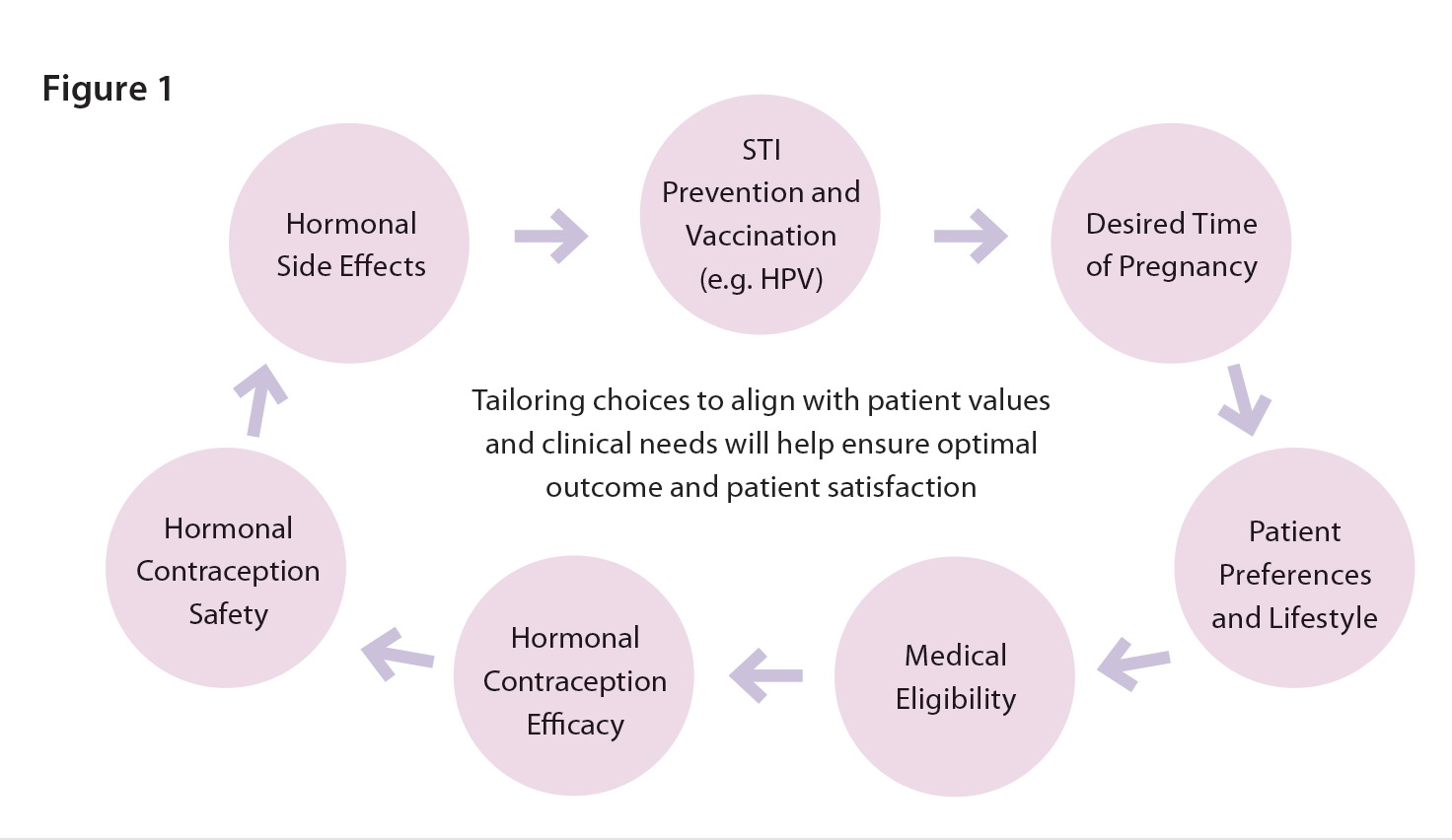

So, what does this mean for patient-centred care in pharmacy practice?

There are several patient screening tools available (see resources section below) that you can adapt to help determine which contraceptive options may or may not be suitable for your patients. That said, the most important starting point is the conversation itself by focusing on what matters most to the patient. There are several considerations other than just safety and efficacy as we often focus on as pharmacists. (Figure 1)

Start by exploring their reproductive goals. You might start off asking questions like, “When are you thinking about getting pregnant?” or “How important is it for you not to become pregnant right now?” (11) There is also a very interactive patient facing tool available on https://www.itsaplan.ca/ where the patient can navigate independently, which can facilitate your conversations prior to prescribing. If the patient is leaning towards oral contraceptives, it’s helpful to explore lifestyle preferences and desired features, such as low androgenicity for those concerned with acne or facial hair.

For patients with chronic conditions like stable hypertension or diabetes, progestin-only options may be more appropriate. Among these, drospirenone offers a few advantages: it’s more forgiving when it comes to missed doses and provides consistent ovulation suppression due to its longer half-life. In contrast, norethindrone has long been the go-to postpartum option but requires strict adherence to timing. While norethindrone remains a trusted and reliable option, drospirenone offers newer features that may better align with the needs of some patients, particularly those looking for more flexibility or greater reassurance in terms of efficacy.

In summary, with expanded prescribing authority and full PharmaCare coverage in B.C., pharmacists are well-positioned to play a greater role in contraceptive care. Yet time constraints, a crowded product landscape, and limited clinical tools can make decision-making challenging. While COCs remain common, progestin-only pills, especially newer options like drospirenone, offer safe, effective alternatives for many patients. By understanding key progestin differences and applying structured, patient-centered approaches, pharmacists can confidently tailor contraceptive choices to individual needs and clinical contexts.

Checklists:

- Patient Screening Tool: https://www.pharmacy.ca.gov/publications/patient_screening_tool_consumers_english.pdf

- Patient Self-Assessment Questionnaire for HC: https://ubccpe.instructure.com/courses/3681/pages/1-dot-2-tools-and-resources?module_item_id=77946

- HC Assessment (PAR) 2021 Update_0.pdf (Med Sask 2023): https://medsask.usask.ca/sites/medsask/files/2023-06/(BC)

- Black, A. JOGC 2015.The Cost of Unintended Pregnancies in Canada: Estimating Direct Cost, Role of Imperfect Adherence, and the Potential Impact of Increased Use of Long-Acting Reversible Contraceptives

- https://www.bcpharmacists.org/ppmac

- https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/health/health-drug-coverage/pharmacare-for-bc-residents/what-we-cover/prescription-contraceptives

- Baird DT, Glasier AF. Hormonal contraception. N Engl J Med. 1993 May 27;328(21):1543-9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199305273282108. PMID: 8479492.

- Cooper DB, Patel P. Oral Contraceptive Pills. [Updated 2024 Feb 29]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430882/

- Edwards M, Can AS. Progestins. [Updated 2024 Jan 10]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK563211/

- Milsom I, Korver T. Ovulation incidence with oral contraceptives: a literature review. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2008 Oct;34(4):237-46.

- Brown S, Eisenberg L. The best intentions: unintended pregnancy and the well-being of children and families. Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 1995.Finer LB, Zolna MR. Unintended pregnancy in the United States: incidence and disparities, 2006. Contraception 2011;84:478-85. Trussell J et al. Burden of unintended pregnancy in the United States: Potential savings with increased use of long-acting reversible contraception. Contraception 2013;87:154–161.

- Black A et al. The Cost of Unintended Pregnancies in Canada: Estimating Direct Cost, Role of Imperfect Adherence, and the Potential Impact of Increased Use of Long-Acting Reversible Contraceptives. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2015;37(12):1086-1097.

- Canadian Contraception Consensus (Part 3 of 4): Chapter 8 – Progestin-Only Contraception. Black, A et al. JOGC, Volume 38, Issue 3, 291.

- Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada. (2018, September). It’s a plan – How effective is my birth control? Retrieved July 11, 2025, from https://www.sexandu.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Its-a-Plan-How-Effective-is-my-Birth-Control-E-1.pdf

- Drospirenone. Product Monograph. https://pdf.hres.ca/dpd_pm/00070310.PDF

- Norethindrone. Product Monograph. https://pdf.hres.ca/dpd_pm/00046339.PDF

- Barbieri RL. Drospirenone vs norethindrone progestin- only pills. Is there a clear winner? OBG Management. 2022;34(2):10-12.

- Trischuk, T and Crawley, A. RxFiles Academic Detailing. (2023, February). Combined hormonal contraceptives (CHCs) & oral contraceptives (OCs): Comparative summary chart [PDF]. RxFiles Academic Detailing Program. https://www.rxfiles.ca/RxFiles/uploads/documents/members/CHT-OCs-Color.pdf

- WHO Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use – 5th Edition. 2015.

- Rice, C. (2006). Selecting and monitoring hormonal contraceptives: An overview of available products. U.S. Pharmacist, 6, 62–70. Retrieved from https://www.uspharmacist.com/article/selecting-and-monitoring-hormonal-contraceptives-an-overview-of-available-products