By Fawziah Lalji, BSc(Pharm), PharmD, FCSHP, ACPR, RPh

Epidemiology

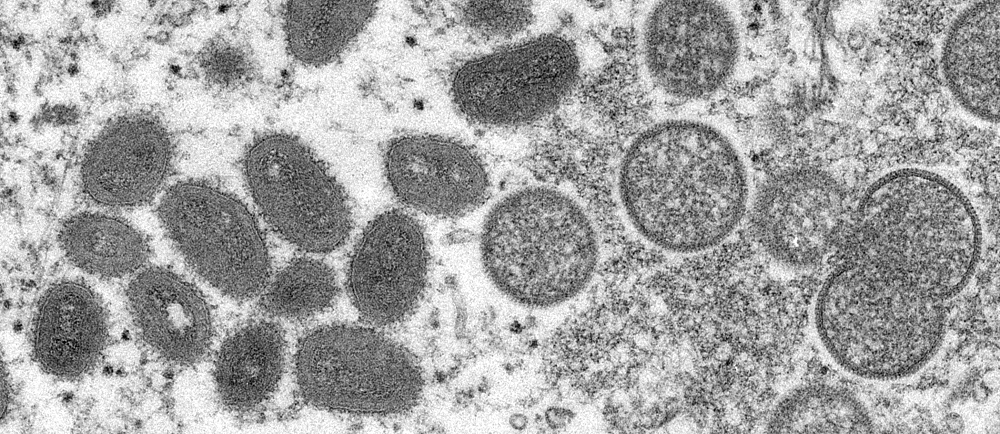

Monkeypox virus is a member of the Orthopoxvirus genus in the family Poxviridae, which includes variola virus (smallpox), cowpox, and others.1 Monkeypox is a zoonotic disease with transmission primarily occurring from animals, such as rodents and primates, to humans.2 Limited human-to-human transmission has been observed amongst close contacts of those infected with monkeypox.

The virus can transmit through contact with bodily fluids, wounds on the skin or internal mucosal surfaces, respiratory droplets, or contaminated objects.2 Monkeypox is not known to be sexually transmitted, but outbreak close contact with a case of monkeypox has been known to be a risk factor for acquiring the infection.1,2 In the current outbreak, it is believed that inoculation of the virus to skin and mucosal surfaces by direct, sexual or skin to skin contact, as well possibly through fomites such as towels, bedding, and sex toys are potential routes of transmission.

Two distinct clades of monkeypox have been identified: the West African clade, which is associated with milder clinical presentation and mortality (~ 1% case fatality ratio), and the Congo Basin (Central African) clade, which has been associated with greater human-to-human transmission and higher mortality (case fatality ratio 1-10%).3,4

In 2021, 15 countries reported confirmed human monkeypox cases, with the majority of these cases being identified in Africa – that is, countries where monkeypox is endemic, such as Nigeria, Central African Republic (CAR), Cameroon, and Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC).1 The balance of these cases were individuals who travelled outside of monkeypox endemic areas to the United States, the United Kingdom, Israel, Benin, South Sudan, Singapore.5

The current 2022 epidemic represents the first multi-country outbreak outside of the continent of Africa.6 Initial detection was in the UK in early May – a family cluster of 3 cases, with one case having a recent travel history to Africa. By July 18, at least 13.340 confirmed cases from 69 non-endemic countries had been reported according to the World Health Organization, with the majority (86%) of cases from Europe. Confirmed cases have also been reported from the African Region (n=73; 2%), the Region of the Americas (n=381; 11%), Eastern Mediterranean Region (n=15; <1%) and Western Pacific Region (n=11; <1%).6 The first monkeypox cases in Canada were reported on May 19 2022, in Montreal and, as of July 18, 539 cases of monkeypox have been confirmed in Canada (299 Quebec, 194 Ontario, 2 Saskatchewan, 12 Alberta and 32 British Columbia).7

Genomic studies in UK and Portugal have linked the recent outbreak with the West African clade.6 Demographic information and personal characteristics are only available for some of the WHO-reported cases, and 99% are men aged 0 to 65 years (Interquartile range: 32 to 43 years; median age 37 years), of which most self-identify as gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men (gbMSM).7 Though the reported cases thus far have been primarily among gbMSM, it is essential to note that anyone can become exposed and infected. The recent cases among gbMSM are thought to be related to shared social networks and participation in large events that may have facilitated transmission.8

Clinical Characteristics and Diagnosis

The incubation period for monkeypox ranges from 5–21 days, although typically, it is between 7–14 days.9,10 The disease is often mild, self-limiting and resolves within 14-21 days.9 Clinical presentation of monkeypox can be similar to smallpox but milder. Symptoms usually begin within five days of infection with fever, chills, intense headache, muscle aches, back pain, and rash. Unlike smallpox and chickenpox, individuals with monkeypox also have swollen lymph nodes. The characteristic rash occurs 1 to 5 days after the initial onset of symptoms, usually beginning on the face and spreading throughout the body, often to the extremities (75% of cases have a rash on palms of the hands and soles of feet) rather than the trunk, and mucous membranes (oral or genital areas). The rash/lesions begin as macules and further develop into papules, vesicles, pustules, and then form crusts. In the current outbreak, monkeypox cases have an atypical presentation with skin lesions occurring in crops at the site of inoculation, which explains why they are predominantly oral, genital, and/or anal lesions; patients do not always have a fever or systemic symptoms.6,11

Due to the similarity in clinical symptoms between monkeypox and chickenpox, healthcare providers often face difficulties diagnosing cases based on clinical symptoms alone. Additionally, cross-protective antiviral immunity among adults who received childhood smallpox vaccination may lead to asymptomatic, mild or unrecognizable disease symptoms.12

The differential diagnosis of monkeypox includes other poxviruses and herpesviruses (this includes chickenpox). Often diagnosis is made presumptively, based on clinical presentation and disease progression. The preferred laboratory test is polymerase chain reaction (PCR) detection of viral DNA, followed by confirmation of positive results by sequencing and/or PCR testing at the National Microbiology Laboratory. The best specimens are from skin, fluid, or open crusts - if these are present, BCCDC recommends collecting directly from skin lesions, or biopsy. For individuals who do not have skin lesions, oropharyngeal swabs, or nasopharyngeal swabs are to be collected; EDTA blood and urine can also be considered for testing. In general, antigen and antibody detection methods are not recommended due to the serological cross-reactivity among orthopoxviruses and the potential for false positive results among people recently or previously vaccinated against smallpox.12

Infection Control

Infection prevention and control measures need to be put in place for suspected monkeypox cases.10 Thus, airborne, droplet and contact precautions are to be implemented, in addition to following routine infection prevention and control practices such as wearing medical masks, performing hand hygiene, wearing gowns, gloves, and eye protection. Preferred room placement is an airborne infection isolation room (i.e., negative pressure room). For environmental infections control, standard cleaning and disinfecting of equipment and surfaces is sufficient, but soiled laundry is handled with gloves to avoid contact with lesion material.

Treatment and Prevention

Currently, there are no proven treatments specifically for monkeypox. Most cases are mild and require supportive treatment based on symptoms (e.g., fever control, hydration).13 The antivirals cidofovir and brincidofovir (pro-drug of cidofovir), which work by inhibiting viral DNA polymerase, have been evaluated within in-vitro and in-vivo animal models with some effectiveness.13 In the treatment of CMV infections, nephrotoxicity or other serious adverse events have not been observed with brincidofovir, suggesting a more favourable safety profile compared to cidofovir. Although the data on safety and efficacy are limited, the FDA approved brincidofovir for treatment of smallpox in 2021. Tecovirimat (ST-246), an inhibitor of the viral envelope protein p37 that blocks the ability of virus particles to be released from infected cells, is another antiviral that could be used for monkeypox. However, there is no data on its effectiveness in humans.14 These three antivirals may be considered in severe cases of human monkeypox on a case-by-case basis as “off-label” use.

Another potential monkeypox treatment, available in the USA, is intravenous vaccinia immune globulin (VIG).9,12 Once again, use of VIG for monkeypox or smallpox has not been tested in humans and there is no data on effectiveness against either virus. As such, the use of VIG for monkeypox treatment would need to be used for special populations such as patients with severe monkeypox infection or as prophylaxis in exposed individuals with T-cell immunodeficiency, for whom smallpox vaccination is contraindicated.

Smallpox vaccines used during the global smallpox eradication programs may provide some protection against monkeypox. However, international smallpox vaccination programs ended in 1980 when smallpox was declared eradicated, and vaccination for travel ended in 1982. Canadians born in 1972 or later have not been routinely immunized against smallpox (unless immunized for travel or work-related risks). For those who have been previously vaccinated for smallpox (i.e., eligible for vaccine in 1980 or earlier), the degree of protection conferred from the smallpox vaccine against monkeypox infection may be up to 85% (5), however the durability of protection and the degree of protection against the current strain of monkeypox remains unknown.

In the USA, there are currently 2 licenced smallpox vaccines: JYNNEOSTM (also known as Imvamune® or Imvanex®) and ACAM2000®. Imvamune® is also licensed for monkeypox, and this is the vaccine that Health Canada maintains a limited stockpile of, and would be available to Provinces and territories on a case-by-case basis.

Imvamune® is a Modified Vaccina Ankara-based (MVA) virus that was developed as a safer, third-generation smallpox vaccine. Like the previous smallpox vaccines, it is a live, attenuated vaccine. Imvamune® is capable of replicating to high titers in avian cell lines such as chicken embryo fibroblasts, but it has limited replication capability in human cells.15 This non-replicating nature of the vaccine differentiates it from the older generation, live smallpox vaccines. Initially authorized for use in Canada in 2013 for smallpox, it further received authorization in late 2020 for immunization against smallpox, monkeypox and related orthopoxvirus infections in adults 18 years of age and older determined to be at high risk for exposure.16

Imvamune® contains trace amounts of host (egg) cell DNA and protein, tromethamine, benzonase, ciprofloxacin and gentamicin.16 No preservative or adjuvant is added to the formulation.16 The primary series is administered subcutaneously in 2 doses of 0.5mL (0.5 x 108 infectious units), given 28 days or 4 weeks apart.17 Booster dose is administered 2 years after the primary series and is one dose of 0.5mL (0.5 x 108 infectious units). Contraindications include patients who are hypersensitive to this vaccine or to any ingredient in the formulation and individuals who show hypersensitivity reactions after receiving the first dose of the vaccine.17

Imvamune® is stored frozen at -20°C ± 5°C or -50°C ±10°C or -80°C ±10°C. After thawing at room temperature, the vaccine should be used immediately or can be stored at 2°C –8°C for up to 2 weeks prior to use.16,17 Refreezing is not permitted once thawed. The product is available as a single-dose vial that should be gently swirled for 30 seconds to ensure homogeneity upon thawing, prior to use.16,17

NACI Recommendations and Evidence

The National Advisory Committee on Immunization (NACI) recommends vaccination in the following populations:17

Post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) for adults with recent exposure:

A single dose of the Imvamune® vaccine may be offered to individuals with high-risk exposures to a probable or confirmed case of monkeypox, or within a setting where there is ongoing transmission. PEP should be provided as soon as possible, preferably within four days after last exposure, but can be offered as late as 14 days after exposure; in this latter scenario vaccination may reduce the symptoms of disease but may not prevent disease.17 The latter recommendation is based on historical studies of the older generation smallpox vaccines, whereby the median effectiveness in preventing disease with vaccination is 93% if given within 0-6 hours, 90% if given within 6-24 hours, 80% if given 1-3 days after exposure.18 PEP should not be offered to symptomatic persons who meet the definition of suspect, probable or confirmed case.

A second dose may be offered to individuals who have ongoing risk of exposure after 28 days.17 Once again, the second dose should not be offered to individuals who are symptomatic (i.e., meet the suspect, probable or confirmed monkeypox case definition).

For individuals who had received a live replicating 1st or 2nd generation smallpox vaccine in the past and sustained a high-risk exposure to a probable or confirmed case of monkeypox, a single dose of Imvamune® PEP may be offered (i.e., as a booster dose).17

Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) for adults at high risk of occupational exposure in a laboratory research setting:17

Imvamune® PrEP may be offered to personnel working with replicating orthopoxviruses that pose a risk to human health (smallpox or monkeypox) in laboratory settings and those at high risk of occupational exposure. If Imvamune® is used, two doses should be given at least 28 days apart. A booster dose may be offered after two years if the risk of exposure extends beyond that time.17 This recommendation does not apply to clinical diagnostic laboratory settings at this time due to the very low risk of transmission.

For immunocompetent individuals who have received a live replicating 1st or 2nd generation smallpox vaccine and who are at high risk for occupational exposure, a single dose of Imvamune® may be offered (i.e., as a booster dose), rather than the two dose primary vaccine series).17 This single Imvamune® dose should be given at least two years after the latest live replicating smallpox vaccine.

The evidence base behind NACI’s recommendations for PEP and PrEP for adults is outlined in the sections below.

There is one phase 3 human study indicating the efficacy of Imvamune® vaccination against monkeypox infection or disease; most of the data is limited to immunogenicity studies.18 However, it should be noted that there is no established level of the correlate of protection, therefore the interpretation of the decline or boosting of immune responses remains unclear. In addition, clinical protection from symptoms of vaccinia infection may not be indicative of protection against monkeypox.

In a Phase 3, randomized, open-label active-controlled non-inferiority trial, 440 smallpox vaccine naïve adults were randomly assigned to receive: (1) two doses of Imvamune® at weeks 0 and 4, followed by one dose of the older generation, live/replicating smallpox vaccine at week 8 or (2) one dose of the older generation, live/replicating smallpox vaccine at week 0 alone.18 Imvamune® immune responses (binding and neutralization) were detectable by week 2. At week 6 after the second dose, immune responses (neutralizing antibody titers) were much higher in the Imvamune® arm (GMT=153.5) than those seen with the one-dose of the previous generation, replicating/live vaccine (GMT=79.3). At the time of peak titres, 100% of participants in the Imvamune® group had seroconverted and 97.3% of participants in the older generation group had seroconverted. At week 4 (a time point when previous the generation vaccine has historically been considered to be protective), seroconversion rates were similar between both groups. As a surrogate marker of efficacy, the investigators assessed the incidence of major cutaneous reactions in the two arms. At day 14, the median lesion area in the Imvamune® group was 0mm and the older generation smallpox vaccine group was 76mm, generating an area attenuation ratio of 98.2 (95% CI: 97.7-98.4) and meeting the prespecified threshold of over 40%. These data would suggest similar efficacy of the non-replicating vaccine compared to the replicating smallpox vaccine. Of note, there were considerably fewer adverse events in the Imvamune® arm compared to the traditional smallpox vaccine arm.

Previous vaccination with Imvamune® prevented the formation of a full major cutaneous reaction in the majority of participants (77.0%) after receiving the older-generation smallpox vaccine at week 8, as compared with a rate of full major cutaneous reaction of 92.5% in the older-generation vaccine arm. The maximum lesion area of the major cutaneous reaction was significantly reduced (by 97.9%) when vaccinia vaccination (i.e., older generation smallpox vaccine) was preceded by Imvamune® vaccination. These data, in addition to similar data from smaller immunogenicity studies would support the use of Imvamune® as a booster for individuals who have previously received the older-generation smallpox vaccine.21-23

To determine waning of immunity with time, Phase 2 studies evaluated immune responses after one or two doses of Imvamune® and showed that they declined after 2 years. This led to the current recommendation of a booster dose being administered after year 2 providing the risk is ongoing.21-23

The product monograph states that the safety of Imvamune® has been reported from 20 clinical trials where 13,700 vaccine doses were given to 7,414 subjects.16 The most common local adverse events following immunization (AEFI) were pain, erythema, induration and swelling. The most common systemic AEFI were fatigue, headache, myalgia, and nausea. Most of the reported AEFIs were of mild to moderate intensity and resolved within the first seven days following vaccination.

The safety of Imvamune has not been assessed in large clinical trials and therefore its safety data is limited. In some of the studies, cardiac adverse events of special interest were reported to occur in 1.4% (91/6,640) of Imvamune® recipients, 0.2% (3/1,206) of placebo recipients who were smallpox vaccine-naïve and 2.1% (16/762) of Imvamune® recipients who were smallpox vaccine-experienced. Among the cardiac events reported, 28 were asymptomatic post-vaccination elevation of troponin-I, 6 cases were symptomatic with tachycardia, electrocardiogram T wave inversion, abnormal electrocardiogram, electrocardiogram ST segment elevation, abnormal electrocardiogram T wave, and palpitations (none of the 6 events were serious). No confirmed case of myocarditis, pericarditis, endocarditis or any other type of cardiac inflammatory disease (or related syndromes) were recorded.

In summary, the newer generation smallpox vaccine shows protection against monkeypox with a favourable safety profile. But risks versus benefits of protection should be discussed with a healthcare provider, with a full discussion of the potential risk of recurrent myocarditis for individuals with a history of myocarditis/pericarditis linked to a previous dose of live replicating 1st and 2nd generation smallpox vaccine and/or Imvamune®.

1. Petersen E, Kantele A, Koopmans M, Asogun D, Yinka-Ogunleye A, Ihekweazu C, et al. Human Monkeypox: Epidemiologic and Clinical Characteristics, Diagnosis, and Prevention. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2019 Dec;33(4):1027,1043. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2019.03.001.

2. Fine PEM, Jezek Z, Grab B, Dixon H. The Transmission Potential of Monkeypox Virus in Human Populations. Int J Epidemiol. 1988 Sep 01;17(3):643,650. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/17.3.643.

3. Beer EM, Rao VB. A systematic review of the epidemiology of human monkeypox outbreaks and implications for outbreak strategy. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019;13(10):e0007791.

4. World Health Organization (WHO). Monkeypox Fact Sheet. Geneva: WHO; 2019. Accessed 18 May 2022. https://w w w.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/monkeypox

5. Bunge EM, Hoet B, Chen L, et al. The changing epidemiology of human monkeypox—A potential threat? A systematic review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2022;16(2):e0010141.

6. World Health Organization (27June 2022). Disease Outbreak News; Multi-country monkeypox outbreak in non-endemic countries: Update. Available at: https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2022-DON393 Accessed July 6, 2022

7. Canada - Monkeypox outbreak update. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/diseases/monkeypox.html Accessed July 6, 2022

8. WHO Monkeypox: public health advice for gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men, 25 May 2022. Available from: https://www.who.int/news/item/25-05-2022-monkeypox--public-health-advice-for-gay--bisexual-and-other-men-who-have-sex-with-men. Accessed June 18, 2022

9. Monkeypox. The Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security. Available from: https://www.centerforhealthsecurity.org/our-work/publications/2022/monkeypox Accessed June 18, 2022

10. Monkeypox. BC Centre for Disease Control. Available from: http://www.bccdc.ca/health-professionals/clinical-resources/monkeypox Accessed June 22, 2022

11. Adler H, Gould S, Hine P, Snell L, Wong W, Houlihan C. Clinical features on management of human monkeypox: a retrospective observational study in the UK. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022; (online)

12. US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Monkeypox Signs and Symptoms. Updated July 16, 2021. Accessed June 18, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/symptoms.html

13. McCollum AM, Damon IK. Human monkeypox. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58(2):260-267.

14. Russo AT, Berhanu A, Bigger CB, Prigge J, Silvera PM, Grosenbach DW, et al. Co- administration of tecovirimat and ACAM2000TM in non-human primates: Effect of tecovirimat treatment on ACAM2000 immunogenicity and efficacy versus lethal monkeypox virus challenge. Vaccine. 2020 Jan 16;38(3):644,654.

15. Volkmann A, Williamson AL, Weidenthaler H, Meyer TPH, Robertson JS, Excler JL, et al. The Brighton Collaboration standardized template for collection of key information for risk/benefit assessment of a Modified Vaccinia Ankara (MVA) vaccine platform. Vaccine. 2021 May 21;39(22):3067,3080.

16. Product monograph: IMVAMUNE® Smallpox and Monkeypox Vaccine [Internet]. Copenhagen (DK): Bavarian Nordic [updated 2021 Nov 26; cited 2022 Jun 2]. Available from: https://pdf.hres.ca/dpd_pm/00063755.PDF.

17. NACI Rapid Response - Interim guidance on the use of Imvamune® in the context of monkeypox outbreaks in Canada. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/phac-aspc/documents/services/immunization/national-advisory-committee-on-immunization-naci/guidance-imvamune-monkeypox/guidance-imvamune-monkeypox-en.pdf. Accessed June 18, 2022

18. Pittman PR, Hahn M, Lee HS, et al. Phase 3 efficacy trial of modified vaccinia Ankara as a vaccine against smallpox. N Engl J Med 2019;381:1897–908.

19. Massoudi MS, Barker L, Schwartz B. Effectiveness of postexposure vaccination for the prevention of smallpox: results of a delphi analysis. J Infect Dis. 2003 Sep 16;188(7):973,976. doi: 10.1086/378357.

20. An Open-Label Phase II Study to Evaluate Immunogenicity and Safety of a Single IMVAMUNE Booster Vaccination Two Years After the Last IMVAMUNE Vaccination in Former POX-MVA-005 Vaccinees [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): ClinicalTrials.gov [updated 2019 Mar 13]

21. Vollmar J, Arndtz N, Eckl KM, Thomsen T, Petzold B, Mateo L, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of IMVAMUNE, a promising candidate as a third-generation smallpox vaccine. Vaccine. 2006 Mar 15;24(12):2065,2070. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.11.022.

22. A Randomized, Double-blind, Placebo-controlled Study on Immunogenicity and Safety of MVA-BN (IMVAMUNE™) Smallpox Vaccine in Healthy Subjects [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): ClinicalTrials.gov [updated 2019 Mar 6; cited 2022 Jun 6]. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/results/NCT00316524?term=pox-mva-005&draw=2&rank=2.

23. Greenberg RN, Hay CM, Stapleton JT, Marbury TC, Wagner E, Kreitmeir E, et al. A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Phase II Trial Investigating the Safety and Immunogenicity of Modified Vaccinia Ankara Smallpox Vaccine (MVA-BN®) in 56-80-Year-Old Subjects. Plos one. 2016 Jun 21;11(6):e0157335. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0157335.