A BCMJ paper published in May 2023 examined prescribing patterns using PharmaNet data and calculated the climate impact of inhalers in the Fraser Health region

By Kevin Liang, MD, CCFP; Darryl Quantz, MFPH, MPH, MSc

The greenhouse gas emissions of the Canadian healthcare system is among the highest in the world, and pressurised metered-dose inhalers (pMDIs) contribute significantly to this carbon footprint. Because pMDIs use liquefied gases called hydrofluoroalkanes (HFAs) as propellants to deliver medication to the lungs, they release potent greenhouse gases into the atmosphere on actuation and if disposed of improperly.

A recent BCMJ paper published in May 2023 examined prescribing patterns using PharmaNet data and calculated the climate impact of inhalers in the Fraser Health region— the most populous health region in British Columbia. Using the available data, the researchers also estimated the prevalence of short-acting ß2-agonist overuse in patients with asthma—a powerful indicator of poor asthma control and a significant source of emissions.

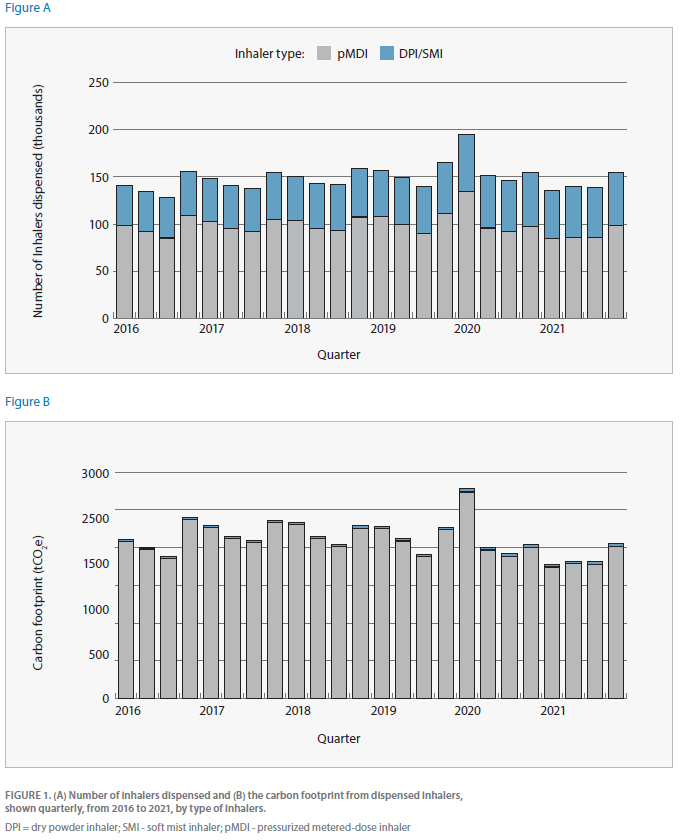

The results show that from 2016 to 2021, more than 3.56 million inhalers were prescribed for Fraser Health region residents; an average of 394,094 pressurised metered-dose inhalers and 199,536 dry powder inhalers/soft mist inhalers were dispensed per year.

The resulting carbon footprint of inhalers was 8,478 tCO2e per year, and pressurised metered-dose inhalers accounted for more than 98 per cent of the footprint. To put this in context, the annual average measured emissions from the Fraser Health region, which includes 174 buildings with 13 acute care hospitals in 2021, over the same six-year period was 38,951 tCO2e. Patients are prescribed a higher proportion of pMDIs compared to low-carbon alternatives that have similar efficacy. Switching to dry powder inhalers (DPIs) when clinically appropriate can significantly reduce emissions.

The article highlights the clinical concerns associated with pMDIs, such as suboptimal inhaler technique and difficulties in determining when the inhaler is empty. DPIs and soft mist inhalers offer improved medication deposition and once-a-day dosing, which can enhance adherence. The study also emphasises the prevalence of short-acting ß2-agonist overuse, which is associated with poor asthma control and increased exacerbation risks.

How community pharmacists can help

By Valeria Stoynova, MDCM, FRCPC, MHPE; Celia L. Culley, BSP, ACPR, PharmD

Climate change is affecting the health of British Columbians as part of a global trend towards adverse health outcomes.1 Every year, climate-related events such as wildfires, heat domes, and floods cause morbidity and mortality, disproportionately affecting our most vulnerable populations.1 This year is no exception; the 2023 wildfire season includes the largest fire in B.C.’s history, covering an area greater than Prince Edward Island and leading to evacuations and disruptions in healthcare delivery.2

Paradoxically, many healthcare interventions needed to keep our patients healthy — including medications — can exacerbate the climate crisis by creating outsized carbon emissions. We know that the Canadian healthcare system accounts for 4.6 per cent of the national greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, a quarter of which are related to prescription and non-prescription medications — inhalers among them.3 In their recent paper, Liang et al. elegantly capture the scope of inhaler-related carbon footprint in the Fraser Valley through a retrospective review of community inhaler dispensing.4 Their alarming findings highlight the medication-related practices that are contributing to our GHG emissions and model potential strategies to decrease this footprint at the prescriber level. This begs the question: how can we, as healthcare providers, do our part to provide high quality patient care while simultaneously minimizing our environmental impact?

Pharmacists are trusted voices in the patient’s care team. As accessible healthcare professionals with expertise in medication management, pharmaceutical supply chains, and drug shortages, pharmacists and pharmacy technicians are well positioned to positively influence healthcare delivery. Healthcare organizations are increasingly recognizing the key contributions of pharmacy professionals in providing climate conscious healthcare with calls to action published in major pharmacy journals,5,6 pharmacy-specific Environmental Sustainability Taskforces,7 and national step-by-step guides on low-carbon sustainable pharmacy practice.8

While the potential contributions are manifold, we propose here five small steps with a big impact you can take in your community pharmacy practice today to mitigate the climate impact of therapy, while continuing to provide high quality, patient-centered care.

Pharmacy professionals play a central role in providing climate-conscious care. High yield actions include prioritizing low-carbon inhalers when feasible, reviewing inhaler technique, optimizing patients’ disease control, and safe inhaler disposal. Although the climate crisis is creating new challenges for the delivery of healthcare, we can take immediate action to protect our patients by mitigating some of the climate impact while continuing to provide high quality, patient-centered care.

- The Lancet Countdown on Health and Climate Change – Policy brief for Canada. Published October 2021. Accessed July 7, 2023 from https://policybase.cma.ca/link/policy14455#_ga=2.33259062.965326161.1649441743-1454976172.1649282066

- Kulkarni A, What Happens After The Donnie Creek Wildfire, now larger than P.E.I., stops burning? CBC News. July 3, 3023. Accessed July 7, 2023 from https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/donnie-creek-wildfire-aftermath-1.6892294

- Eckelman MJ, Sherman JD, MacNeill AJ. Life cycle environmental emissions and health damages from the Canadian healthcare system: An economic-environmental- epidemiological analysis. PLoS Med. 2018;15(7): e1002623. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal. pmed.1002623

- Liang KE, Yao JA, Hui P, Quantz D. Climate impact of inhaler therapy in the Fraser Health Region 2016-2021. BCMJ. 2023;65(4):122-127.

- Beechinor RJ,Overberg A, Brown CS, Cummins S, Mordino J. Climate change is here: What will the profession of pharmacy do about it?. AJHP. 2022;79(16):1393-1396. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajhp/zxac124

- Roy C. The pharmacist’s role in climate change: a call to action. CPJ. 2021;154(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/1715163521990408

- Canadian Society of Hospital Pharmacists. Call for expression of interest - sustainability task force. Published February 7th, 2023. Retrieved July 7th, 2023 from https://www.cshp.ca/Site/Content/News/news-items/Call-Sustainability-TF.aspx)

- CASCADES. Climate Resilient, Low Carbon Sustainable Pharmacy. Retrieved July 7, 2023 from https://cascadescanada.ca/resources/climate-resilient-low-carbon-sustainable-pharmacy-playbook/ CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)”

- Myrdal PB, Sheth P, Stein SW. Advances in metered dose inhaler technology: Formulation Development. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2014;15(2):434-455. doi: 10.1208/s12249-013-0063-x

- Jeswani HK, Azapagic A. Life cycle environmental impacts of inhalers. J Clean Prod. 2019;237:117733 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.117733

11. Stoynova V, Culley C. Detailed Inhaler Carbon Footprint Chart. Version February 2, 2023. Retrieved July 7, 2023 from https://cascadescanada.ca/resources/tools-templates/#inhalers

- Hargreaves C, Budgen N, Whiting A et al. A new medical propellant HFO-1234ze: reducing the environmental impact of inhale medicines. Thorax. 2022;77(1).

- Usmani OS, Lavorini F, Marshall J et al. Critical inhaler errors in asthma and COPD: a systematic review of impact on health outcomes. 2018;19(10) https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-017-0710-y